Wednesday, 31 January 2024

From School to Plumbing and Back Again!

Thursday, 25 January 2024

Urban Planning, Anyone?

Saturday, 20 January 2024

Collins Bay's 'Aunt Maude'

Albert Edward Rowley was born in Somerset, England, living in Collins Bay for 70 years. He was section foreman for the Grand Trunk Railway at Collins Bay in 1919, and contracted the Spanish Flu in November, 1918, requiring hospitalization at Kingston's Hotel Dieu Hospital. One sordid story involves him finding a dead trespasser who'd been walking the tracks west of Collins Bay. Likely a World War I veteran, the train killed him even though a bullet war wound found at autopsy did not. Bert was known to drive an old '29! Retiring in 1946, he was an award-winning member of the Kingston Stamp Club in the mid-1950s.

He married Gertrude Maude Waller in October, 1930 and though they had no children, she was 'auntie' to over 500 children that passed through her Sunday School classroom. Their golden wedding anniversary was celebrated at Edith Rankin on October 19, 1980. Bert died at 98 years old on May 18, 1986. Aunt Maude died on February 18, 1988 at the age of 90.

Thursday, 18 January 2024

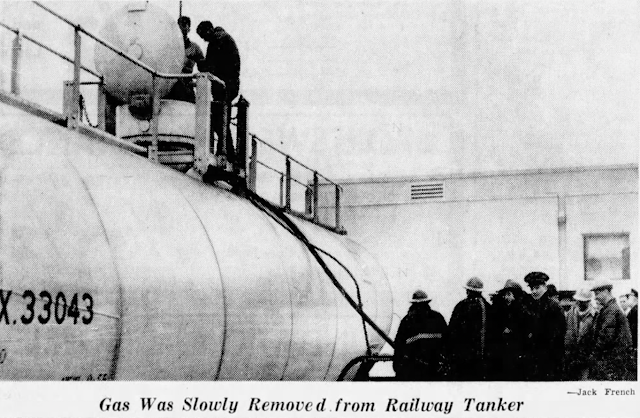

Kingston's Coal Gasification Plant - History

Monday, 15 January 2024

From Clarence to Charles by Air!

- the Ontario Street switchman's shanty is still in place. The shanty was removed between 1950 and 1963.

- the PUC propane tanks are already in place. The tanks were installed in February/March, 1950.

- three CP passenger cars were adjacent to the North Street roundhouse. Mixed train service ended along with the end of the steam era, circa 1957.

- Canadian Army Staff College training building across Ontario Street from Fort Frontenac are not yet in place. Older buildings on site were demolished around 1952 and the new building built in 1954.That narrowed it down!

- the Imperial Oil bulk tanks on Rideau Street were a very visible spotting feature. The tanks in Barry's photo matched the 1953 year layer exactly.

- the ships and barges moored at Canadian Dredge & Dock also matched 1953 exactly!

As a result of this very enjoyable, brief bit of detective work, I'm calling this aerial photo analysis done, and as a result, I believe Barry's photo was taken from on high in 1953!

- north of the North Street roundhouse - 6 freight cars

- at roundhouse - 3 passenger cars and 3-4 freight cars

- Shell bulk tanks - 3 freight cars, probably tank cars

- yard - 7 cars

- station - 2 cars on spurs, 10 at freight shed, the car cleaner's flat car

- Swift dock area - 1 car

- Wellington St. freight shed - 6 and 7 boxcars

- yard - 22+ cars

- PUC propane tanks - 1 propane tank car

- Crawford coal - 3 hopper cars

- Ontario St feed mill - 1 car off-spot

- Topnotch feed mill - 2 box cars

Sunday, 14 January 2024

James Richardson and the Richardson Family's Long Legacy in Kingston

Marc begins...

The sprawling enterprise of James Richardson & Sons has been based in Winnipeg for almost 100 years. It’s an immense privately owned family-run business, now headed by a member of the 5th generation. Dealing in businesses as diverse as insurance, investing, oils and gas, agriculture and real estate, it's a global behemoth, and incredibly successful. The relatively low-profile Richardson clan is worth something like $6.55 billion and are consistently ranked in the country’s top ten.

Some in Kingston may be surprised to know that the story began here, and that the Richardsons were long a Kingston institution. The family was aways philanthropic by nature, and although they have moved on, the city is awash in memorials, particularly in the hospitals and at Queen’s University, where many of them were educated.

It’s a very interesting family and much has been written on the individuals, their stately homes, their benefactions and their business enterprises. It’s hard to condense the whole story down. It’s also a bit confusing, with a lot of James, Henrys and Georges, with a couple of Agneses! This “précis” is not for the faint of heart!

The founder of the Canadian family and the firm which bears his name, James Richardson (1819-92), arrived in Kingston in 1823 from Ireland and was apprenticed to a tailor. Over time he discovered that often his clients could not afford to pay him in cash but gave him grain instead, which led him to gradually move into that industry. Over the next decades he built a grain-shipping and export business into a major concern. James Richardson & Sons was formed in 1857. By the 1860s he was a very wealthy man, and as a measure of his success he built for himself and his family a fine brick home at 100 Stuart Street, in a new suburb near the hospital. He built a large grain elevator on the Kingston waterfront in 1882 and by the following year was shipping wheat to England. By the time he died in 1892, the firm he and his sons operated was a major player in the Canadian grain trade. The Richardson elevator burned down in November 1897 and was replaced by a second, larger one that was a familiar sight for several decades. It also burned, in December 1941, while it was in the process of demolition. The Holiday Inn is on the site today.

In the next generation his sons George (1852-1906) and Henry Wartman (1855-1918) carried on the business. George was President from 1892-1906. In 1879 he built a large Victorian home called Windburn on Gordon Street, within sight of the home on Stuart where he had grown up. His brother Henry Wartman was President of the firm from 1906-1918. He and his family lived in stately Alwington House, off King Street at the western edge of town.

He was a noted local businessman with involvement in many enterprises: to name a few, he was President of the Street Railway Company, the Kingston Hosiery Company, and the Kingston Feldspar and Mining Company. Mrs. Richardson’s sister married Dr. Walter Connell and they occupied a very nice home nearby at 11 Arch Street, adding to the numerous relations in the Queen’s neighbourhood. Henry Wartman was named to the Senate and died at Alwington in 1918. He and his wife Alice Ford Richardson were major philanthropists and donated the funds for Richardson Laboratory at for the joint benefit of Queen's University and Kingston General Hospital, completed in 1925.

Their children were all wealthy, of course, but seemed less inclined to involve themselves in the core family business. Their son Henry came to live in a large brick home at 102 Stuart Street, next door to the original family residence. Henry was President of the Weber Piano Factory (S&R/Smith-Robinson building). The original family house next door was eventually occupied by his sister Eva, who married Thomas Ashmore Kidd (1889-1973), a grocery broker who also had considerable success in politics: MLA 1926-40, Speaker of the Ontario Legislature, MP 1945-49. He was also the Grand Master of the Orange Lodge.

When the Kidds lived at 100 Stuart Street, their extensive back yard and gardens were noted for their careful landscaping and were the scene of numerous social and fundraising activities. After World War I, the house was converted into a convalescent hospital for returning soldiers. A brother to Henry and Eva was John, who inherited Alwington and lived there for a time but eventually bounced back and forth between there and Winnipeg. Another sister, Bessie, married successful contractor T.A. McGinness and in 1924 they built Stone Gables on King Street West, on a piece of property cleaved off the Alwington estate.

The two Stuart Street houses remain and have long been used by Kingston General Hospital (known as Kidd House and Richardson House, of course). After a long period as a private home, in the 1980s or 1990s Stone Gables became part of the Regional Headquarters complex for the Correctional Service of Canada. Its future disposition seems uncertain. And Alwington House was tragically burned in December 1958, with the loss of two lives, while Mrs. Dorothy Richardson was still in residence. The house remains were demolished and the property sold; Alwington Place was laid out where perhaps Kingston’s most celebrated home had once stood.

As noted above, Henry Wartman’s brother George (1852-1906) moved upon his marriage to a large new house at the corner of Gordon and Alice (today, University and Bader Lane). He and his wife had a number of children who grew up in the sprawling Victorian home. Son George Taylor (1886-1916) enjoyed a brilliant academic and athletic career at Queen’s and seemed destined for great things within the family grain business; he was named Vice-President in 1910. However, he was tragically shot by a sniper in France in 1916.

In his will, he left the bulk of his fortune to his sister Agnes and brother James with instructions to use it to fund a number of initiatives for the betterment of Kingston citizens. The money was carefully invested, and primarily under Agnes’ stewardship, was allocated to some very worthwhile enterprises. The Richardson Beach bathhouse, the George Richardson Memorial Stadium, and allocations for the stimulation of art and culture in Kingston were a few of the results. Agnes (1880-1954) married Dr. Frederick Etherington in 1921 and they made their home in her old family house where she had lived since birth. Etherington had had a brilliant career at Queen’s and during WWI ran a field hospital in Egypt and France. After he returned to Kingston, he became a Professor of Surgery and was for many years the Dean of Medicine at Queen’s. Etherington Hall (1959) is named for him.

Soon after their marriage and their taking up residence in the old house, the Etheringtons decided to build a new home on the same site. The result was the very graceful Georgian-style home which stands today (with many additions). The new house was perfect for entertaining and the house became a hub of the Kingston Arts and Literature scene. Over the years, Agnes funded speakers, visiting professors, and the purchase of works of art. The Etheringtons had no children, and on Agnes’ death in 1954 she bequeathed the house to be renovated and used as an Art Museum, which of course it remains today. Following WWI, Agnes also erected a convalescent home and recreational facilities (including a small golf course) on Fettercairn Island (today Richardson Island) in Indian Lake near Chaffey’s Locks.

Agnes’ only surviving brother was James (1885-1939) who appeared to inherit the drive and foresight of his ancestor who had first created the fortune. He moved into company administration following studies at Queen’s, and became President in 1919. A man of great drive and ambition, he bought out the inherited interests from all his cousins and came to dominate the firm to the extent that he became, in the public mind, the only Richardson.

He took the company to great heights. Recognizing the importance of the West to the core family grain business, he supervised the move of the Kingston executive office to Winnipeg in 1923, and relocated there. Prior to the move to Winnipeg, the company’s head office was in the building at 243 King Street East, now occupied by Empire Life. It had been there from 1914, when it took over from Regiopolis, and was succeeded there by the Oddfellows organization. Prior to 1914, he had been on the southwest corner of Princess and Ontario (present Cornerstone).

George was a giant in Canadian industry, a visionary businessman with significant side interests in radio and commercial air travel. Under his stewardship, the firm became the largest grain business in the British Empire. Queen’s named him Chancellor of the university in 1929, a position he held until his untimely death a decade later. Richardson Hall, a Queen’s building constructed in 1954 a few doors away from where he had grown up, was named in his honour.

Upon his death in 1939, an unusual thing happened. His widow Muriel took over as President and proceeded to run the company with great success until her death in 1973. Their descendants continue to operate the company to this day. They are a very well known family in Winnipeg, and have long supported many Winnipeg institutions including the Winnipeg Ballet. For many years the only “skyscraper” in the city was the 34 storey Richardson Headquarters building, erected in 1969.

One son, James, was an MP and member of Cabinet under Pierre Trudeau. Another, George, was company president for many years and was also the last Canadian Governor of the Hudson Bay Company. Daughter Agnes (1920-2007) married William Benedickson, MP and Senator, and was Queen’s Chancellor (her father’s old position) from 1980-96. Agnes Benedickson Field is named in her honour.

Few if any families have left a larger imprint on Kingston.

-my thanks to Marc Shaw for generously sharing this!

James Richardson Grain Elevator - History

RICHARDSON'S KINGSTON ELEVATOR

CONSTRUCTION PROGRESS

- The last of 650 spiles, driven into the bottom in clusters, were completed in ten days on January 20, under contractor J.E. O'Shea.

- The cement foundation boxes for masonry buttresses were being filled on January 23, resting on the spiles.

- Tinning by the Pedlar metal roofing company of Oshawa was underway on April 21.

- The north-side marine leg of the elevator, capable of unloading 9,500 bushels/hour and was placed on May 3. The south side's two vessel-loading legs were capable of vessel loading at a rate of 20,000 bu/hr.

- The railway spur was being completed May 11.

- Equipment was tested on May 13, with only minor work required on main floor.

- The steamer Orion was to be unloaded on the evening of May 13, with another 12 vessels waiting to unload. The sloop Echo arrived on May 16 with 22,000 bushels of barley from lake ports. Orion again discharged 13,000 bushels of wheat from Chicago at the elevator on June 2. The sloop Madcap unloaded 1,800 bushels of oats on June 10.

- Dredging by a government dredge was underway near the elevator on June 1.

ELEVATOR FIRE AND DEMOLITION

Frankel Brothers of Toronto was awarded the contract by Vice-President John B. Richardson to demolish the elevator. Considered by Richardson to be not of economic value and in danger of becoming a waterfront eyesore, the Kingston elevator caught fire on the evening of Tuesday, December 23, 1941. Noticed first by an Ordinary Seaman O'Neil of Kingston, on duty at the nearby naval training base formerly the Richardson office, at the foot of Princess Street. The sailors formed a volunteer fire brigade organized by the Naval Lieutenant Sherman Hill, commander of the training base. To save their training vessel Magedoma, formerly the Fulford Yacht of Brockville anchored a mere 150 feet away from the elevator, they kept the sailing vessel's decks wet to prevent sparks landing. Several large freighters were anchored at winter berths only one hundred yards away! The Kingston fire department deployed 6,000 feet of hose, tapping hydrants at the CP station and on Queen and Princess Streets. The elevator was completely destroyed, before its demolition that was already underway, was completed. The original octagonal office, housing a wartime naval training centre at the time, was not damaged.

.jpeg)

.jpg)

.jpeg)