Here is my capsule history of CLC. Photos are mostly from the Queen's University Archives, published in my book with permission.

THE EARLY YEARS

In 1854, railway locomotive construction commenced along Ontario Street. The Ontario Foundry built five locomotives for the GTR in 1856 at Mississauga Point. By the year of Confederation, a full-page advertisement for the Canadian Engine and Machinery Company touted the company’s ability to produce locomotive, marine and fire engines. The plant would have more name changes and different owners, and more than 300 locomotives were built in the next few years. In the 1870’s, with the change from broad-gauge to standard-gauge, broad-gauge locomotives with inside connected cylinders which could not be converted, were replaced with new builds. By 1881, the plant was in the hands of well-known Kingstonians, until Scotland’s Dubs & Company took over its management in 1887, building more than 170 locomotives. Between 1887 and 1904, the plant was alone in Canadian locomotive manufacturing. Special Edition of Kingston's Daily British Whig profiling local businesses and their principals, 1909 (above).

Increased competition from the railways’ own Montreal locomotive shops – Canadian Pacific’s Delorimier and the GTR’s Pointe St Charles meant bankruptcy filing and liquidation by Dubs in 1900. The factory was closed for eight months while buyers were sought. Kingstonians purchased the operation for $60,000, reorganizing under the name The Canadian Locomotive Company (CLC) in February, 1901. Nearly 500 locomotives were produced in 11 years – as many as in the previous 50 years! William Harty would remain President until 1911.

CP’s first D10’s were completed in July, 1905. There would be 502 built, 68 at Kingston, including CP 1095 which is displayed opposite City Hall (above, with your humble blogger and siblings in August, 1969 - L.C. Gagnon photo). In June, 1911 the Jarvis group – Canadian and British bankers – added ‘Limited’ to CLC and 2,060 locomotives would be manufactured under that name. There was plant expansion in 1912, including a red-brick erecting shop along Ontario Street. Despite the name changes, generations of Kingstonians would come to call the growing lakefront plant simply “The Loco.” The long expanse of red brick of the 1914 erection shop facing Ontario Street house in-plant erection shop tracks that exited the plant between machine shops. March, 1970. (Queen’s University Archives, George Lilley Fonds, V25.5-38, 39, 41)

THE FIRST WORLD WAR

Europe was then on a war footing, and British financing was hard to secure. Imperial Russia saved the struggling plant with its order for 50 2-10-0 Decapods for the Trans-Siberian Railway. Delivered in 1915-1916 via New York and the newly-completed Panama Canal to Vladivostok, a total of 400 were produced, as were wartime shells and other munitions. Unfortunately, John “Jock” Harty, signatory to the Russian contract, contracted the Spanish Flu while in London during a business trip. Harty, board secretary before becoming President, was a well-known Queen’s University man, and the Queen’s hockey arena would later bear his name. This October 7, 1921 Whig article mentioned the resolution of a strike:

Employing 1,500 men, having quintupled its workforce in less than 20 years, the plant turned out Mountains, Northerns and Santa Fe types for Canadian National Railways, the GTR’s successor and one of CLC’s best customers. The Santa Fes in particular weighed 655,040 pounds, marking the first applications of Vanderbilt tenders in Canada. Considered the largest locomotives in the British Empire at the time, the Santa Fes would have been quite a sight to see as they made their way to the Outer Station and out onto the mainline. That same routing was taken by CN’s boxcab diesel 9000 on November 20, 1928 thence a test run to Montreal reaching speeds of 65 mph. Matching unit 9001 was delivered on April 15, 1929 to be mated with the 9000. The latter unit made its first revenue run from Montreal to Toronto on the second section of the International Limited on September 26, 1929. CLC's office building at Ontario and William Streets was built in 1928. Locomotive orders were tied to railways’ profits and the between-war years’ Great Depression took an understandable toll. Except for some specialized heavy industry equipment such as ore classifiers, and industrial locomotives, CLC had no orders on the books between 1932 and 1936.

THE SECOND WORLD WAR

Another world war led to another surge in orders. On July 28, 1942 CP 2396 became the 2,000th locomotive produced by CLC. It was proudly but only temporarily painted and photographed with a commemorative crest on its tender and the number 2000 on its maroon-painted running boards (below). That year saw the plant’s highest sales volume in company history.

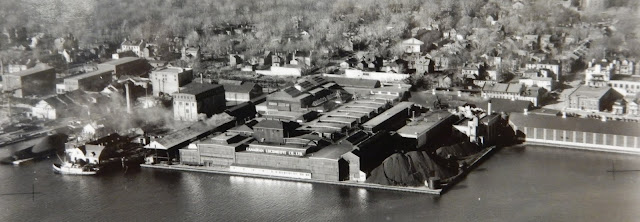

CLC’s war effort produced warship gun mounts for two-pounder “pom-pom” anti-aircraft guns and depth-charge throwers. A VE-Day victory parade float comprised a stationary firebox-boiler and dozens of plant workers aboard. Many of the workers were women, making up one-sixth of the plant’s wartime labour force. Aerial view of the plant, by now completely land-locked by Lake Ontario in foreground, the Kingston Shipyards at left and houses fronting the other side of Ontario Street up to King Street and downtown Kingston. September, 1948. (Queen's University Archives, George Lilley Fonds V25.6-6-9)

POST-WAR TRANSITION

Concluding CLC’s G5 Pacific-type production for CP, G5d 1272 poses outside the plant. CP 1272-1301 were the last 30 of CP’s 100-locomotive G5 class. More were planned, but dieselization negated that planning. April 3, 1948. (Queen’s University Archives, George Lilley Fonds, V25.5-2-212):

The last steam locomotive built for a Canadian railway was CP 1301, delivered on August 20, 1948. Diesel-electric locomotives were the future, and with General Motors building a new plant in London in 1950, and Montreal Locomotive Works partnering with Alco-GE to produce their designs in Canada, CLC would need a major partner in order to compete.

CLC believed it was ready for the steam-to-diesel transition period which Canadian railways were approaching, and that the company was alert and ready to adapt its output to meet their requirements. Whitcomb-built CN 75-ton 7800-series switchers are stored in the shadow of the CLC plant along Ontario Street. Not accepted by CN, their CN logos were papered over before return to the U.S. 1948. (Queen’s University Archives, George Lilley Fonds, V25.5-2)

The plant was sold to Fairbanks Morse in the plant’s centenary year of 1950, after CLC President W.J. Langston reached out to FM and successfully negotiated rights to all FM designs and their opposed-piston engine. American Robert Morse, Jr. became President. The plant had to be modernized. Foundry shops, blacksmith forges, steam hammers and boiler shops with riveters dating to steam days were obsolete. The last steam engine built in Kingston, indeed anywhere in Canada, was one of 120 built for Indian State Railways in 1955-56 with the final one was completed in September, 1956. India's High Commissioner, President of the Canadian Commercial Corporation and other officials pose with the first of the Indian locomotives, produced and shipped under the Colombo Plan on March 18, 1955. (Queen's University Archives, George Lilley Fonds, V25.5-36-149-1, degraded negative):

CLC would build 325 diesels between 1946 and 1968. Industrial equipment product lines were also offered such as Akins classifiers for mining, General American evaporators for pulp and paper, high-capacity kilns for metallurgy, and horizontal filters for sewage plants. CLC held exclusive Canadian rights to manufacture General American, Conkey and Louisville industrial equipment.

A red-letter day for CLC dawned on August 1, 1951. CLC had 1,000 employees with an annual payroll of $2.5 million at the time. A huge crowd assembled around City Hall and Ontario Street for Diesel Day, as the new CLC/FM line premiered. CLC C-Liners 7005-7006, actually CP 4064-4065 re-lettered for CLC, sat on CP trackage for cab tours. (Vintage Kingston Facebook group photo - above).

Steam still handled diesels, as diminutive D4’s dragged new CP diesels over the former K&P line to Tichborne. To heed bridge weight restrictions, a few freight cars separated the heavy diesels, and at Tichborne they were switched out for furtherance to Montreal via Smiths Falls, with the tiny steam train continuing on its way to Renfrew! In steam days, locomotives were always built north-facing with cabs at the south end of the erecting bays. In the case of freight diesels, this was radiator-end north. While many CLC-built steam locomotives lasted 40 years, CN’s CLC diesels lasted only a quarter as long. Officials pose with newly-built CN 8704, now coupled to the head-end of an eastbound freight train at the Outer Station on its way to Montreal for acceptance testing by CN. The train’s locomotive was likely temporarily removed for this publicity photo. May, 1952. (Queen’s University Archives, George Lilley Fonds, V25.5-30-262-30)

A harbinger was CN 3000, later renumbered 2900. Built at FM’s Beloit, Wisconsin plant, the demonstrator, along with CP 8900, were shipped to CLC. When CLC’s Vice-President of Manufacturing handed over the unit’s throttle handle to CN’s J. Ernest Kerr on August 19, 1955, neither of them could know it would be scrapped a mere 11 years later. CP would order 21 of the long units. CP 8900 was received by CP Vice-President D.S. Thomson on July 12. Inconsistent performance by CLC’s led to few repeat orders. CN H24-66 3000, built and shipped north from Fairbanks Morse’s Beloit, WI plant is inspected by officials while on dual-gauge track across from City Hall. August 19, 1955 (Dave Stevens photo, Don McQueen collection)

A minor fire made the Kingston Whig-Standard pages on March 29, 1956:

THE FINAL YEARS

Only seven small locomotives left the plant between 1961 and 1966. Sales projections for the last five years of the sixties were no more than $160,000 per year, eclipsed by $600,000 in parts and $260,000 forecast for industrial locomotives. In 1965, Fairbanks Morse (Canada) Limited lettering replaced CLC’s on the plant’s wall. Despite production of export diesels for India in 1967, the last locomotive to leave the plant was Calcutta Port Commissioners’ D61 on July 12, 1968. Reorganization in 1968, labour unrest, strike votes, accusations of sabotage and a “runaway” plant switcher up the branchline to an eventual collision with boxcars at Elliott Avenue soured relations between plant management. Nearing the end of an era, workers picket CLC near Ontario and Gore Streets. Former Saskatchewan premier Tommy Douglas visited the strikers to lend his support. May 2, 1969. (Queen’s University Archives, George Lilley Fonds, V25.5-47-196)

In February, 1969 President C.F. Morris was replaced by C. Zillis in St. Johnsbury, VT. Zillis never travelled north to visit the plant. At the time of an April 11 strike vote, CLC workers contended they were making 60 cents an hour less than their counterparts at Alcan or DuPont. The strike affected 120 workers. No agreement was reached on the company’s ultimatum and operations ceased as of July 1, 1969. The last product of the plant, a marine engine, was loaded on to a Halifax-bound flatcar on June 27.

(Above) CLC in twilight: the plant is quiet as Fairbanks Morse letters have replaced CLC lettering on the façade facing Ontario Street. March, 1970 (Queen’s University Archives, George Lilley Fonds, V25.5-38, 39, 41).

No comments:

Post a Comment

I'm happy to hear from you. Got a comment about the Hanley Spur? Please sign your first name so I can respond better.