Saturday, 28 August 2021

Kingston's Tour Train

Wednesday, 25 August 2021

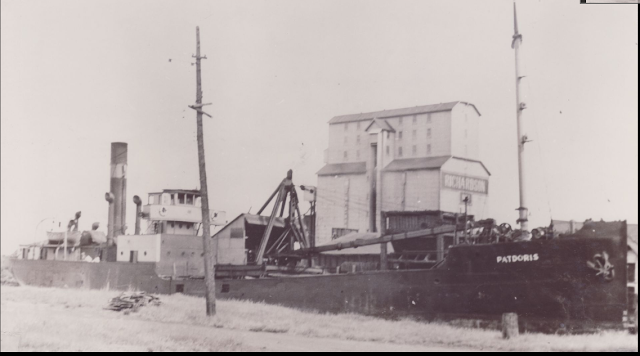

Coal Boat 'PatDoris'

From the Toronto Maritime History Society 'Scanner' newsletter: The steam collier PATDORIS, (a) ARDGATH, (b) YORKMINSTER, which was operated onwards frm 1924 in the Lake Ontario coal trade by J. F. Sowards of Kingston. She later belonged to the Maple Leaf Steamship Company Ltd. of Montreal and we have one report to the effect that she was sold for scrap in 1946 although it is not confirmed. PatDoris is shown on the Kingston waterfront with the Richardson No. 1 grain elevator in the background, undated but pre-1941.

Bob Crothers sailed as a teenager during the mid 1930s on the PatDoris, bringing coal several times per week from Oswego, NY. Bob describes the work on coal boats in his own words:

She was a fast boat, she could run 22 miles per hour and it took her two hours to cross the lake from Oswego to Kingston. The crew, except for the Captain and one or two older sailors, were local teenage boys. Most of them lasted only a week. The loading at Oswego was fast. She was a bulk carrier and the coal was dumped from the coal trestles through chutes into the hold. That did not take more than a few hours, and then she sailed back to Kingston.

We had only a few hours rest between the loading and unloading work. At the coal dock beside the Kingston Water Works, a crane did the bulk of the unloading with a grab-shovel. Two big steel shells that could be opened and closed at the end of the cable. The crane dumped each load in the coal bins on the dock. Besides the bins, there were also mountains of coal all over the place.

The crane could only do so much until there were a few feet of coal left at the bottom of the hold. The crew had to shovel the coal manually to the middle of the hold so that the grab-shovel could pick up a load. After a while that no longer worked and we had to shovel the coal by hand into the grabber… That was by far the worst! The work was not only physically demanding, but it was dirty, lots of coal dust, and in the summer with high humidity in the hold, it was almost impossible to do. The pay was good, at least in the eyes of us young boys, but most of us did not stay long. For the Captain and older crew it was not too bad, as long as they had enough younger boys willing to do the dirtiest work.”

Saturday, 14 August 2021

Coal Dock at Rockwood Asylum

Wednesday, 11 August 2021

Irish Burial Site Dig at KGH

Close by our laboratory at KGH was a marker to these remains, now the site of KHSC's largest-ever construction project. Other markers are sited along Kingston's waterfront. Aerial view, July 1964 (top photo) - before construction of the Kidd and Davies wings, FAPC and extension to Connell wing. Barely recognizable except for the heating plant! (Queen's University Archives, Kingston Whig-Standard fonds).We were told that this project would begin in 2015! I intend to visit the newly completed wing with my therapy dog on the Access Bus - that's how far in the future the completion of this most ambitious project seems to be projected! In this 1989 aerial view, the enlarge Connell Wing and Kidd/Davies wings dominate the scene:

Archeological dig to relocate remains from Irish burial site at KGH

Historians aim to learn about the typhus epidemic and Great Famine of 1847

Please Share - Media Release August 11, 2021

KINGSTON, ONTARIO - Work is now underway at Kingston Health Sciences Centre’s (KHSC) Kingston General Hospital (KGH) site to uncover a sad chapter in world history. An archeological firm has begun the process of unearthing and relocating the remains of Irish immigrants who contracted and died of typhus while escaping Ireland’s Great Famine in 1847.

An estimated one million Irish died in what is known as the Great Irish Famine (also known as the Great Irish Hunger and Great Irish starvation) and another two and a half million were forced to leave their homeland between 1847 and 1852. An estimated 1,400 Irish immigrants died shortly after arriving in Kingston and were buried on the grounds of Kingston General Hospital (just to the west of KGH’s original Watkins wing.)

The work to relocate the individuals buried at KGH is an integral part of KHSC’s KGH site redevelopment project, which will see the demolition of a number of older buildings, to make way for the construction of a new patient tower. The new tower will house new operating rooms, a new emergency department, laboratories, labour and delivery department, neo-natal intensive care unit and two inpatient floors.

“While our redevelopment project is essential for KHSC to continue to meet the highly-specialized needs of patients from across southeastern Ontario, we recognize the level of care and sensitivity required to relocate a burial site such as this,” says Krista Wells Pearce, KHSC’s vice-president of Planning. “We have been working closely with representatives of the local Irish community as well as with leadership from the Anglican, Presbyterian and Catholic churches, to not only bless the site before the work began, but to respect the dignity, faith and culture of those who were buried here nearly 175 years ago.”

In 1847, during the Great Famine, landlords were made responsible by the British government for the welfare of their Irish tenants. So, many landlords forced tenants off the land and aboard ships destined for North America. Irish citizens weakened by hunger and infected with typhus, were forced to come to Canada on these overcrowded ships. The close quarters and poor ventilation onboard, contributed to the quick spread of the disease. Many died before ever arriving in Canada, giving their vessels the grim nickname “coffin ships.”

“Around 50,000 Irish immigrants came to Kingston and about 1,400 men, women and children died of typhus and were buried at KGH,” says Tony O’Loughlin, Founder & President of Kingston Irish Folk club and the Kingston Irish Famine Commemoration Association. “At the time, KGH was a small, seasonally operated hospital and had fewer than 50 beds. It was totally overwhelmed by the large numbers of critically ill Irish patients arriving that summer.”

Thomas Kirkpatrick, Kingston’s first mayor, and the local Board of Health set up large ‘fever sheds’ mainly along the waterfront near Emily Street, however, these were insufficient to meet the demand and filled quickly. In an effort to control the spread of the disease, the deceased were buried as quickly as possible. Remains were brought nightly by death carts to the grave site on the grounds of KGH.

“At that time the majority of citizens in Kingston were Irish and many brought the newly arrived sick individuals into their homes leading to further spread of the disease. About 300 Kingstonians also died while trying to help the newly arrived Irish. Those individuals were buried in Kingston’s upper cemetery in what is now McBurney Park. Mrs. Martin (who held the position of first Matron at KGH) and her daughter, as well as Sister Mary Magorian, a member of Religious Hospitallers of St. Joseph who served Hotel Dieu Hospital are among those that contracted and died from typhus while helping the Irish,” says O’Loughlin.

A small number of the remains, along with a large statue to mark the sacred ground, were moved to St. Mary’s cemetery during hospital expansion in 1966. However many individuals remain interred at KGH, including underneath a parking lot and under and around several buildings. Historic plaques were erected on the site, but they include incorrect information stating all of the remains had been moved from KGH grounds in 1966. The confirmation that the burials remain on the site was done by Ground Truth Archaeology in 2020.

“Working with Infrastructure Ontario, we’ve hired a Canadian archeological firm, ASI, who bring expertise in cultural heritage conservation and experience working on both hospital and Irish famine projects,” says Wells Pearce. “They are treating this work with the respect it deserves, not only in honour of those that are buried here, but also from a greater historical perspective. They have told us that the excavation and respectful study of the remains is a unique opportunity, unprecedented in Canada, to learn more about their lives during and prior to the events of 1847.”

As part of their work, ASI has also consulted with representatives of local Indigenous communities before starting their work.

The remains of the Irish will be re-interred in local cemeteries in the future. Kingston Health Sciences Centre has also committed to creating a public monument to these individuals once construction of the new patient tower is complete. It is expected that the excavation work will continue through the summer and into late autumn.

Kingston General Hospital aerial view, July 1964. Before construction of the Kidd and Davies wings, FAPC and extension to Connell wing. Barely recognizable except for the heating plant! (Queen's University Archives, Kingston Whig-Standard fonds).

The Angel of Mercy Monument was dedicated in 1894 on the grounds of the Kingston General Hospital. It marked the burial site of over 1,400 individuals: approximately 1,000 who were previously quarantined at Grosse Isle, but would pass away in Kingston, many at a local fever shed; another 400 were local Kingston residents who contracted typhus at the time.

The Angel is sculpted out of Carrara marble and holds a trumpet and a Bible that is open to the story of the Resurrection. The monument is engraved with the following passage: "In memory of his afflicted Irish compatriots, nearly 1,400 in number, who, enfeebled by famine in 1847-48, ventured across the ocean in unequipped sailing vessels, in whose fetid holds they inhaled the germs of the pestilential ‘ship-fever’ and upon reaching Kingston, perished here, despite the assiduous attention and compassionate offices of the good citizens of Kingston. May the Heavenly Father give them eternal rest and happiness in reward of their patient suffering and Christian submission to His Holy will, through the merits of His divine Son, Christ Jesus, our Lord. Amen’

In 1966, the monument and some of the remains were moved to Kingston’s Upper Cemetery (St. Mary's), approximately two miles away from the original site to make room for an expansion of the General Hospital. There remains a plaque at the rear (morgue) door of the hospital to mark the approximate spot.

Thanks to Marc Shaw for additional information in this post.

Monday, 2 August 2021

The Tugboat 'Rival'

- Tug Rival with overturned Bruce Hudson, barge in Toronto Harbour, 1935.

- Tub Rival on the bottom, Shotline Diving image.

The R-100 over Kingston, 1930

_(I0013039).tif.jpg)